Since Script Frenzy is rapidly approaching, I've been thinking about dramatic structure. These notes aren't authoritative or particularly well researched, but they have gotten me to a starting point.

Jump to my conclusions about how to write a screenplay.

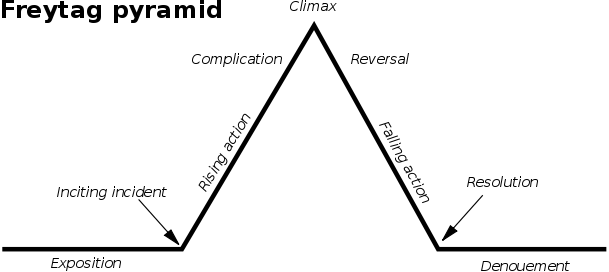

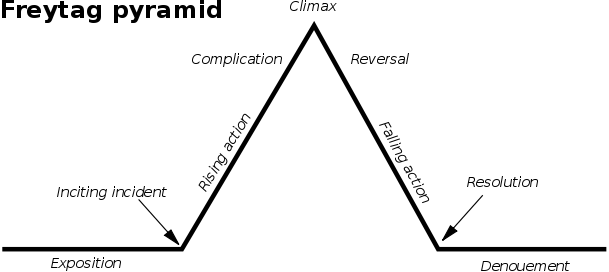

Nineteenth century critic Gustav Freytag, thinking particularly of Greek and Shakespearean drama, articulated a five act dramatic structure. The first act contains the exposition, introduces the characters and setting, and ends with an inciting incident. The second act complicates the problem created by the inciting incident, frustrating the protagonist's efforts. The third act is the climax, in which the fortunes of the protagonist reverse. (In terms of Greek drama, the fortunes of a comic protagonist would go from unlucky to lucky, while the fortunes of a tragic protagonist would go from lucky to unlucky.) In the fourth act, the results of the protagonist's turn of fortune plays out; this may end with a final moment of suspense, such as a confrontation between the protagonist and antagonist which puts the final outcome in doubt. Act five, the denouement, documents the consequences of the resolution, and ties-up any secondary plots. Freytag's dramatic structure is often illustrated as a pyramid.

The five act structure is out of favor in modern drama. Instead, a three act structure is often used, particularly for screenplays. As in the five act structure, the first act of the three act structure established characters and setting, and includes an inciting incident. The second act is the confrontation. The third act contains the climax and denouement. Often the first act is about 30 minutes, the second act about 60 minutes, and the third act about 30 minutes.

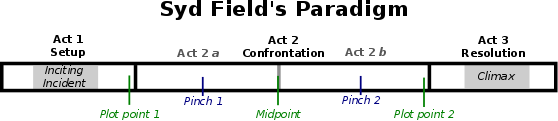

Syd Field, author of the book Screenplay, advocates a four act structure, but his focus is less on the contents of the acts than on the plot points, which punctuate those acts, and things he calls pinches:

Of the structural theories I researched, this one strikes me as providing the most practical help for a screenwriter. It also has the advantage of being conceptually elegant compared to some of the other theories of dramatic structure.

Films are (or were previous to digital cinema) distributed on reels each 8-10 minutes in length. In the early days of film, writers were advised to use a structure that would allow for a natural narrative break at the end of each real. This was particularly important until the late 1920's, because most theaters only had one projector and the audience would have to wait while the projectionist changed reels. Feature films used about eight reels, so they had eight narrative sequences. Frank Daniel, who headed the film programs at Columbia and USC, suggested that using eight sequences of 10-15 minutes is still a reasonable way to structure the narrative of a film. Mr. Daniel died in 1996, but his disciple Paul Joseph Gulino describes the approach in Screenwriting: The Sequence Approach.

Gulino says that structure can be quite variable, and that it's only an aide to help the screen writer keep the audience's attention. (He quotes E.M. Forester: "It has only one merit: that of making the audience want to know what happens next. And conversely it can only have one fault: that of making the audience not want to know what happens next."

) Gulino identifies four main tools—listed in ascending importance/power—to keep the audience asking what happens next:

The sequence approach divides a film into three acts: a first act comprised of two sequences, a second act comprised of four sequences, and a third act of two sequences (though there can be considerable variance in this formula from film to film). Each sequence can be viewed as a mini-movie: asking and resolving a dramatic question (that is, resolving the question in a way that leads organically to the new dramatic question in the next sequence). Gulino lists the eight sequences:

"the dramatic question that will shape the rest of the picture."This is the end of the first act.

The structural models described above are pretty similar. You can cram a lot of movies into their molds. However, they don't give you everything you need to write a screenplay.

Many movies use the following elements to create a satisfying narrative:

Writing a screenplay is a big job. Break down the job into smaller parts. If it helps you, think of of each 8-15 minute sequence as a mini-movie with its own mini-exposition, mini-climax, and mini-resolution.

The techniques articulated by Frank Daniel for creating audience interest—telegraphing, dangling cause, dramatic irony, and dramatic tension—were the most useful practical tips my research found.

Here's a memo executive producer David Mamet sent his writers on The Unit:

TO THE WRITERS OF THE UNIT

GREETINGS.

AS WE LEARN HOW TO WRITE THIS SHOW, A RECURRING PROBLEM BECOMES CLEAR.

THE PROBLEM IS THIS: TO DIFFERENTIATE BETWEEN DRAMA AND NON-DRAMA. LET ME BREAK-IT-DOWN-NOW.

EVERYONE IN CREATION IS SCREAMING AT US TO MAKE THE SHOW CLEAR. WE ARE TASKED WITH, IT SEEMS, CRAMMING A SHITLOAD OF INFORMATION INTO A LITTLE BIT OF TIME.

OUR FRIENDS. THE PENGUINS, THINK THAT WE, THEREFORE, ARE EMPLOYED TO COMMUNICATE INFORMATION — AND, SO, AT TIMES, IT SEEMS TO US.

BUT NOTE:THE AUDIENCE WILL NOT TUNE IN TO WATCH INFORMATION. YOU WOULDN’T, I WOULDN’T. NO ONE WOULD OR WILL. THE AUDIENCE WILL ONLY TUNE IN AND STAY TUNED TO WATCH DRAMA.

QUESTION:WHAT IS DRAMA? DRAMA, AGAIN, IS THE QUEST OF THE HERO TO OVERCOME THOSE THINGS WHICH PREVENT HIM FROM ACHIEVING A SPECIFIC, ACUTE GOAL.

SO: WE, THE WRITERS, MUST ASK OURSELVES OF EVERY SCENE THESE THREE QUESTIONS.

1) WHO WANTS WHAT?

2) WHAT HAPPENS IF HER DON’T GET IT?

3) WHY NOW?

THE ANSWERS TO THESE QUESTIONS ARE LITMUS PAPER. APPLY THEM, AND THEIR ANSWER WILL TELL YOU IF THE SCENE IS DRAMATIC OR NOT.

IF THE SCENE IS NOT DRAMATICALLY WRITTEN, IT WILL NOT BE DRAMATICALLY ACTED.

THERE IS NO MAGIC FAIRY DUST WHICH WILL MAKE A BORING, USELESS, REDUNDANT, OR MERELY INFORMATIVE SCENE AFTER IT LEAVES YOUR TYPEWRITER. YOU THE WRITERS, ARE IN CHARGE OF MAKING SURE EVERY SCENE IS DRAMATIC.

THIS MEANS ALL THE “LITTLE” EXPOSITIONAL SCENES OF TWO PEOPLE TALKING ABOUT A THIRD. THIS BUSHWAH (AND WE ALL TEND TO WRITE IT ON THE FIRST DRAFT) IS LESS THAN USELESS, SHOULD IT FINALLY, GOD FORBID, GET FILMED.

IF THE SCENE BORES YOU WHEN YOU READ IT, REST ASSURED IT WILL BORE THE ACTORS, AND WILL, THEN, BORE THE AUDIENCE, AND WE’RE ALL GOING TO BE BACK IN THE BREADLINE.

SOMEONE HAS TO MAKE THE SCENE DRAMATIC. IT IS NOT THE ACTORS JOB (THE ACTORS JOB IS TO BE TRUTHFUL). IT IS NOT THE DIRECTORS JOB. HIS OR HER JOB IS TO FILM IT STRAIGHTFORWARDLY AND REMIND THE ACTORS TO TALK FAST. IT IS YOUR JOB.

EVERY SCENE MUST BE DRAMATIC. THAT MEANS: THE MAIN CHARACTER MUST HAVE A SIMPLE, STRAIGHTFORWARD, PRESSING NEED WHICH IMPELS HIM OR HER TO SHOW UP IN THE SCENE.

THIS NEED IS WHY THEY CAME. IT IS WHAT THE SCENE IS ABOUT. THEIR ATTEMPT TO GET THIS NEED MET WILL LEAD, AT THE END OF THE SCENE,TO FAILURE - THIS IS HOW THE SCENE IS OVER. IT, THIS FAILURE, WILL, THEN, OF NECESSITY, PROPEL US INTO THE NEXT SCENE.

ALL THESE ATTEMPTS, TAKEN TOGETHER, WILL, OVER THE COURSE OF THE EPISODE, CONSTITUTE THE PLOT.

ANY SCENE, THUS, WHICH DOES NOT BOTH ADVANCE THE PLOT, AND STANDALONE (THAT IS, DRAMATICALLY, BY ITSELF, ON ITS OWN MERITS) IS EITHER SUPERFLUOUS, OR INCORRECTLY WRITTEN.

YES BUT YES BUT YES BUT, YOU SAY: WHAT ABOUT THE NECESSITY OF WRITING IN ALL THAT “INFORMATION?”

AND I RESPOND “FIGURE IT OUT” ANY DICKHEAD WITH A BLUESUIT CAN BE (AND IS) TAUGHT TO SAY “MAKE IT CLEARER”, AND “I WANT TO KNOW MORE ABOUT HIM”.

WHEN YOU’VE MADE IT SO CLEAR THAT EVEN THIS BLUESUITED PENGUIN IS HAPPY, BOTH YOU AND HE OR SHE WILL BE OUT OF A JOB.

THE JOB OF THE DRAMATIST IS TO MAKE THE AUDIENCE WONDER WHAT HAPPENS NEXT. NOT TO EXPLAIN TO THEM WHAT JUST HAPPENED, OR TO*SUGGEST* TO THEM WHAT HAPPENS NEXT.

ANY DICKHEAD, AS ABOVE, CAN WRITE, “BUT, JIM, IF WE DON’T ASSASSINATE THE PRIME MINISTER IN THE NEXT SCENE, ALL EUROPE WILL BE ENGULFED IN FLAME”

WE ARE NOT GETTING PAID TO REALIZE THAT THE AUDIENCE NEEDS THIS INFORMATION TO UNDERSTAND THE NEXT SCENE, BUT TO FIGURE OUT HOW TO WRITE THE SCENE BEFORE US SUCH THAT THE AUDIENCE WILL BE INTERESTED IN WHAT HAPPENS NEXT.

YES BUT, YES BUT YES BUT YOU REITERATE.

AND I RESPOND FIGURE IT OUT.

HOW DOES ONE STRIKE THE BALANCE BETWEEN WITHHOLDING AND VOUCHSAFING INFORMATION? THAT IS THE ESSENTIAL TASK OF THE DRAMATIST. AND THE ABILITY TO DO THAT IS WHAT SEPARATES YOU FROM THE LESSER SPECIES IN THEIR BLUE SUITS.

FIGURE IT OUT.

START, EVERY TIME, WITH THIS INVIOLABLE RULE: THE SCENE MUST BE DRAMATIC. it must start because the hero HAS A PROBLEM, AND IT MUST CULMINATE WITH THE HERO FINDING HIM OR HERSELF EITHER THWARTED OR EDUCATED THAT ANOTHER WAY EXISTS.

LOOK AT YOUR LOG LINES. ANY LOGLINE READING “BOB AND SUE DISCUSS…” IS NOT DESCRIBING A DRAMATIC SCENE.

PLEASE NOTE THAT OUR OUTLINES ARE, GENERALLY, SPECTACULAR. THE DRAMA FLOWS OUT BETWEEN THE OUTLINE AND THE FIRST DRAFT.

THINK LIKE A FILMMAKER RATHER THAN A FUNCTIONARY, BECAUSE, IN TRUTH, YOU ARE MAKING THE FILM. WHAT YOU WRITE, THEY WILL SHOOT.

HERE ARE THE DANGER SIGNALS. ANY TIME TWO CHARACTERS ARE TALKING ABOUT A THIRD, THE SCENE IS A CROCK OF SHIT.

ANY TIME ANY CHARACTER IS SAYING TO ANOTHER “AS YOU KNOW”, THAT IS, TELLING ANOTHER CHARACTER WHAT YOU, THE WRITER, NEED THE AUDIENCE TO KNOW, THE SCENE IS A CROCK OF SHIT.

DO NOT WRITE A CROCK OF SHIT. WRITE A RIPPING THREE, FOUR, SEVEN MINUTE SCENE WHICH MOVES THE STORY ALONG, AND YOU CAN, VERY SOON, BUY A HOUSE IN BEL AIR AND HIRE SOMEONE TO LIVE THERE FOR YOU.

REMEMBER YOU ARE WRITING FOR A VISUAL MEDIUM. MOST TELEVISION WRITING, OURS INCLUDED, SOUNDS LIKE RADIO. THE CAMERA CAN DO THE EXPLAINING FOR YOU. LET IT. WHAT ARE THE CHARACTERS DOING -*LITERALLY*. WHAT ARE THEY HANDLING, WHAT ARE THEY READING. WHAT ARE THEY WATCHING ON TELEVISION, WHAT ARE THEY SEEING.

IF YOU PRETEND THE CHARACTERS CANT SPEAK, AND WRITE A SILENT MOVIE, YOU WILL BE WRITING GREAT DRAMA.

IF YOU DEPRIVE YOURSELF OF THE CRUTCH OF NARRATION, EXPOSITION,INDEED, OF SPEECH. YOU WILL BE FORGED TO WORK IN A NEW MEDIUM - TELLING THE STORY IN PICTURES (ALSO KNOWN AS SCREENWRITING)

THIS IS A NEW SKILL. NO ONE DOES IT NATURALLY. YOU CAN TRAIN YOURSELVES TO DO IT, BUT YOU NEED TO START.

I CLOSE WITH THE ONE THOUGHT: LOOK AT THE SCENE AND ASK YOURSELF “IS IT DRAMATIC? IS IT ESSENTIAL? DOES IT ADVANCE THE PLOT?

ANSWER TRUTHFULLY.

IF THE ANSWER IS “NO” WRITE IT AGAIN OR THROW IT OUT. IF YOU’VE GOT ANY QUESTIONS, CALL ME UP.

LOVE, DAVE MAMET

SANTA MONICA 19 OCTO 05

(IT IS NOT YOUR RESPONSIBILITY TO KNOW THE ANSWERS, BUT IT IS YOUR, AND MY, RESPONSIBILITY TO KNOW AND TO ASK THE RIGHT Questions OVER AND OVER. UNTIL IT BECOMES SECOND NATURE. I BELIEVE THEY ARE LISTED ABOVE.)

© Paul Gorman